One of the most commonly injured ligaments personal trainers may see happen in their athletic clients is the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). ACL injuries continue to be one of the most common injuries in sports today with an estimated of over 200,000 injuries occurring annually according to the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons(AAOS) at a cost of approximately $17,000 per ACL injury. The focus of this article is to review the common causes of ACL injuries, the difference between common ACL surgeries; post-surgical rehabilitation, and evidence-based post-therapy recommendations.

Risk Factors/Mechanism of ACL Injury

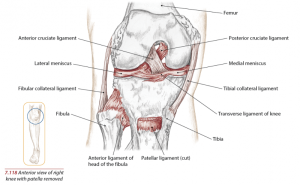

The ACL prevents anterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur, i.e. prevents the tibia from sliding forward relative to the femur. This ligament is commonly injured when the tibia (lower leg bone) is struck while the knee is extended, pushing back on the femur (upper leg bone). Typically the athlete will hear a “pop” and sustain immediate local pain with the inability to bear weight and extend the knee. The risk factors that have been previously studied contributing to ACL injuries for non-contact ACL injuries fall into four distinct categories: environmental, anatomic, hormonal, and biomechanical.4

Many studies have shown that women are more likely to have ACL injuries than men. Landry et al asked 42 elite adolescent soccer players to perform an unanticipated side-cut maneuver while 3D kinematic, kinetic, and electromyographic lower limb data was collected. Females demonstrated greater rectus femoris activity throughout stance and demonstrated less hip flexion during the side-cut test. The researchers concluded that the muscle imbalance activity and reduced hip flexion may all have contributing roles in the higher noncontact ACL injury rates.1

Anatomically, women possess a wider Q-angle—the angle created with the quadriceps and the patella that will be greater with wider hips—than men, which places greater valgus stress on the knees. Furthermore, research indicates there is increased joint laxity within the knee during menstruation.

Hewett et al wanted to examine if neuromuscular training can reduce the incidence of knee injuries. Through his study, he found three neuromuscular imbalances encountered in female athletes. One imbalance is the tendency for the female athlete to be “ligament dominant.” A classic clinical example is the box jump test. Here the athlete is asked to jump off a box. When landing, they demonstrate a valgus knee deformity indicating decreased neuromuscular control and anatomically due to a weaker glute medius.

Biomechanically, according to the research by Jacobs et al, women landing from a jump demonstrated increased valgus potentially increasing the risk for injury. Furthermore, correlations between hip abductor strength and landing kinematics were generally larger for women than men, suggesting that hip abductor strength may play an important role in neuromuscular control of the knee.6

Female athletes demonstrating this valgus will have more stress placed on ligaments to absorb ground reaction forces before muscle activation. Another imbalance is termed “quadriceps imbalance”. With quadriceps dominance, the knee extensors are activated preferentially over the knee flexors to stabilize the knee joints.

The final imbalance is “leg dominance.” Leg dominance occurs when the imbalance of muscular strength and coordination is stronger on one side.2 Electromyographic studies further documented quadriceps dominance and muscular imbalances in the coronal plane. The study showed that female athletes activate quadriceps in an unbalanced manner, compared to male athletes.2

Surgical Interventions For ACL Injuries

Surgeon experience and preference, graft availability, and tolerance to harvest the morbidity determine which graft will be used.3 Two of the common surgeries for ACL reconstruction are the patellar tendon graft and hamstring graft. Sutures are pulled through and the graft is advanced into the femoral tunnel until the mark on the graft is visualized at the entrance of the femoral tunnel. The incision and portals are closed in layers and steristrips and a temporary dressing is applied.

Rehabilitation Management

The goal of physical therapy is to first restore mobility, then promote stability. Rehab is typically divided into four 4-week stages. Between 12-14 weeks post-surgery, light jogging is introduced and continued proprioceptive exercises to prepare for higher-level training. At 16 weeks post-surgery both running and plyometrics are programmed to assist with regaining speed, agility, and power.

Post-Rehabilitation Training

Once discharged from physical therapy, the goal is continued strengthening of hamstrings and hip extensors to continue to reduce stress to the anterior knee since the quadriceps tend to be dominant and biomechanically stronger. Implementation of core strengthening, multi-directional strengthening, and cross-training such as swimming and hiking is fundamental.

Return to Play

Scientific evidence combined with experienced-based empirical evidence has created a new training approach for neuromuscular training. The three essential training components of neuromuscular training are dynamic, biomechanically correcting movement patterns, neuromuscular patterning to correct the neuromuscular imbalances and constant biomechanical analysis both during and after training.5

Returning to sport is contingent on several factors. The average athlete returns to playing sport between 6-9 months post-surgery. The decision to return to competition is individualized and is often based on the input from the “team” including the athlete themselves, physicians, and physical therapists. Athletes must demonstrate pain-free range of motion, possess strength of 85% or greater as compared to the uninvolved leg and pass functional limb testing.

Summary

Female athletes may demonstrate one or more neuromuscular imbalances of ligament dominance, quadriceps dominance, and/or leg dominance. Correction of neuromuscular imbalances is important for optimal movement for the athlete and reduction in knee injuries. By understanding the role the anterior cruciate ligament plays, the biomechanics it serves with dynamic movement, preventive strategies discussed, the personal trainer has the knowledge to be able to work with a client who has gone through ACL reconstruction.

References

1. Roninger, Lori Rochelle. Lower limb gender differences in athletes linked to ACL injuries. Biomechanics. February 2008. Page 11.

2. Hewett, Timothy, Myer, Greg., Ford, Kevin. Dynamic balance: Can neuromuscular training prevent ACL injuries? Biomechanics. Pages: 22-32.

3. Starkey Chad, Johnson, Glen. Athletic Training and Sports Medicine. 4th edition. Jones and Bartlett. Sudbury, Massachusetts. 2006. Pages: 138-142.

4. Letha Y. Griffin , et al. Noncontact Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: Risk Factors and Prevention Strategies. Journal of American Academy Orthopedic Surgeons. Vol 8, No 3, May/June 2000. Pages: 141-150.

5. Myer, Gregory., Ford, Kevin., Hewitt, Timothy. Rationale and Clinical Techniques for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Prevention Among Female Athletes. Journal of Athletic Training. 2004 Vol 39(4). Pages: 352-364.

6. Jacobs, Cale A., Uhl, Timothy., Mattacola, Carl G., Shapiro, Roberto., Rayens, William. Hip abductor function and lower extremity landing kinematics: sex differences. Journal of Athletic Training. 2007. Vol. 42(1). Pages: 76-83.

______________________________________________

Chris Gellert, PT, MPT, CSCS, CPT is the President of Pinnacle Training & Consulting Systems. Gellert offers educational workshops on human movement, home study courses on human movement, and consulting services. As a clinician, author, presenter, he has over 19 years experience having treated and worked with individuals of all ages with various spinal injuries, post surgical conditions, traumatic, and sport specific injuries in industrial rehabilitation, outpatient, and private practice settings. For more information, contact www.pinnacle-tcs.com or call 443-528-0527/(888)586-4188.

______________________________________________

These resources are for the purpose of personal trainer growth and development through Continuing Education which advances the knowledge of fitness professionals. This article is written for NFPT Certified Personal Trainers to receive Continuing Education Credit (CEC). Please contact NFPT at 800.729.6378 or info@nfpt.com with questions or for more information.