Obesity ranks as one of the most serious public health challenges today. Despite the best efforts of fitness/nutrition professionals, as many as 1.6 billion adults currently fit the medical parameters of “overweight”, with a frightening 400 million falling into the obese category. When exercise and prudent nutrition fail to produce a client’s desired results, science may provide some needed additional insight into how hormones and obesity interplay– a major health concern.

The Science of Satiety

We’re most familiar with the roles of ghrelin and leptin in regulating feelings of hunger and satiety, but there are more hormones involved in the process increasing the complexity of our understanding of it.

Peptide YY (PYY3-36), a hormone consisting of 36 amino acids, is secreted in the small intestines and functions in the human body as a satiety signal. Satiety hormones serve to decrease the size of a consumed meal and inform the consumer when they are “full”. This goes hand-in-hand with their function of blocking the endogenous activity that prompts one to continue eating.

Following a meal, Peptide YY begins to circulate in the bloodstream. The hormone ultimately binds to receptors in the brain, which in turn decreases appetite and brings on the sensation of satiety. Peptide YY also acts in the stomach and intestine to slow down the flow of food throughout the GI system.

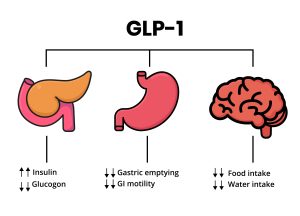

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), a hormone produced in the cells which line the intestines, greatly resembles PYY as it too gets released in response to food intake. The main actions of GLP-1 work collectively to limit postprandial (post-meal) glucose as well as to inhibit motility within the GI tract. Again, paralleling the actions of PYY, GLP-1 fosters regulation of appetite and food intake; a lower quantity of secreted GLP-1 may contribute to the development of obesity.

GLP-1 mechanism of action. Pancreas, Stomach and brain as glucagon-like peptide target organs

Satiety and the Central Nervous System

Most satiety signals interact with specific receptors on those nerves which originate in the gastrointestinal tract, and communicate with the neurological area known as the hindbrain. This region holds responsibility for the execution of our basic survival functions: movement, respiration, consumption, and the sleep cycle. Following externally administered PYY, scientists can detect a change in neurological activity in other areas of the brain as well (specifically the hypothalamus, brain stem, and regions involved in reward processing), further corroborating the belief that PYY directly affects the central nervous system.

Macronutrients Make a Difference

One research study sought to determine whether a diet comprised of low energy density (LED) food sources (what we consider to be an ideal balance of nutritious fruits, vegetables, beans, and lean meats) might facilitate weight loss by acting upon circulating concentrations of PYY. Results of this study suggest that LED diets align with higher circulating concentrations of PYY. This trend seems to hold true during a period of weight loss as well as subsequent weight maintenance. However, experts suggest cautious speculation with regard to the physiological association between LED diets and PYY, since the study’s results did not achieve statistical significance only an observed positive correlation.

Another study sought to determine whether macronutrient composition influences post-consumption levels of PYY in the bloodstream. Over the course of seven days, two subject groups – both classified as obese — followed either a weight-maintaining low-carbohydrate, high-fat (LCHF) diet or a meal plan comprised of low-fat, high-carbohydrate food sources (LFHC).

At the conclusion of the weeklong experiment, data revealed a 55% higher serum level of PYY in those test subjects who followed high fat/low carbohydrate meal plan. Clearly, macronutrient consumption does matter; fats, more so than carbohydrates, stimulate Peptide YY secretion. The quantity of PYY released into the blood seems to depend upon the calories consumed; foods that pack a significant caloric punch will elicit more peptide release.

Not So Simple

Some individuals may struggle with what seems like an oxymoron; how can higher-calorie foods elicit a greater quantity of PYY while simultaneously not contributing to weight gain? As one observes with a ketogenic diet– a meal plan higher in fats–weight loss can still occur if one heeds portion size and incorporates regular exercise. If we think logically of what happens when someone under-consumes at meal time, this does make sense: eating below BMR or even eating too little at a meal will result in continued hunger and a plausible chance of overconsuming calories during the following meal.

The Body Can Tell Time

Personal trainers also certified as health coaches and dietitians often receive requests from clients for “the best foods” to include while attempting to reshape body composition. We try to stress the importance of including all macronutrients, and more importantly, the timing of nutrient intake.

Efforts have been made to determine exactly when PYY levels increase following a meal, and how macronutrients affect the timing of such variations. Scientists assessed eight obese females consuming three meals of equal calories but differing in macronutrient composition: high carbohydrate (HC; 60% CHO, 20% protein, 20% fat), high fat (HF; 30% CHO, 20% protein, 50% fat) and high protein (HP; 30% CHO, 50% protein, 20% fat).

The meals highest in carbohydrates resulted in a sustained postprandial release in PYY throughout the experimental period, i.e. levels released were the same levels maintained throughout the test. Interestingly, the high-fat meal induced a significantly higher increase in postprandial PYY levels, at 15 and 30 min, than the meal containing the most protein.

The post-prandial increase following the high-protein meal peaked more than the high-fat meal after two hours. It seemed evident from these results that the PYY levels brought on by meals higher in both fats and protein induced an ultimately greater level of satiety –and the maintenance thereof— for a greater duration.

PYY Hormones and Obesity

A low concentration of peptide YY in one’s system reflects an increase in appetite and concomitant higher food intake. Physicians might expect to observe this in patients with obesity and/or pre-diabetes; and a fair amount of evidence does exist to suggest that low circulating PYY concentrations predispose an individual to the development and/or maintenance of obesity. While this may very well constitute one of the contributing factors to weight gain, such diminished concentrations fail to serve as the main cause of obesity, since levels diminish after weight gain accumulates. Still, due to its clear appetite-inhibitory effect of PYY, research efforts continue to assess this hormone as a potential therapeutic agent in the treatment of obesity.

Practical Applications and the Future

As personal trainers we possess a strong knowledge of how exercise affects the muscles and body composition. A thorough understanding of how exercise affects energy balance can help fill in any gaps when presenting a training program to a new client.

With no clear understanding of the mechanisms involved in the effect of exercise on appetite regulation, research scientists offer a few possibilities. Potential increases in sympathetic nervous system activity, which in turn elicits the release of catecholamines, may stimulate the intestinal cells to produce PYY as well as GLP-1. Future research endeavors might focus on the specific mechanisms of these actions. In addition, exploring exercise protocols that increase caloric burn without increasing energy intake could pave the way for improving training/weight management success.

References:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4218742/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2670018/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/peptide-yy

https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/358343

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5122107/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17726080/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18544972/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5327759/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24842049/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17928588/

Cathleen Kronemer is an NFPT CEC writer and a member of the NFPT Certification Council Board. Cathleen is an AFAA-Certified Group Exercise Instructor, NSCA-Certified Personal Trainer, ACE-Certified Health Coach, former competitive bodybuilder and freelance writer. She is employed at the Jewish Community Center in St. Louis, MO. Cathleen has been involved in the fitness industry for over three decades. Feel free to contact her at trainhard@kronemer.com. She welcomes your feedback and your comments!