The terms “psoas” and “hip flexor” are common jargon in the health and fitness world, but getting an intimate handle on the specifics may help your clients perform better or even help relieve their back pain. In this article, we’ll discuss the anatomy, the implications in performance and injury, and how to keep the psoas happy and healthy!

The Anatomy of the Psoas

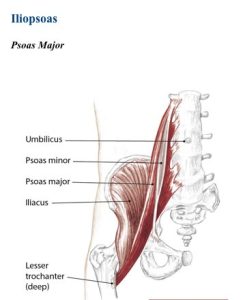

The psoas muscle is part of the iliopsoas group of muscles, commonly and colloquially referred to as “hip flexors”. Pronounced “SO-AZZ”, these pesky muscles actually anchor to our lumbar vertebrae and course down through the back of the pelvis before attaching to the head of the femur. The iliacus lines the inferior pelvic wall and shares an attachment with the psoas major to lesser trochanter, so the two work well together and are often referred to as one.

The psoas muscle is part of the iliopsoas group of muscles, commonly and colloquially referred to as “hip flexors”. Pronounced “SO-AZZ”, these pesky muscles actually anchor to our lumbar vertebrae and course down through the back of the pelvis before attaching to the head of the femur. The iliacus lines the inferior pelvic wall and shares an attachment with the psoas major to lesser trochanter, so the two work well together and are often referred to as one.

The psoas major itself takes nearly three entire 90-degree turns on its way to its tendinous connection at the hip. If anything, this baby is proof of our evolutionary past—that we were not always walking upright and nature had to make some….we’ll say….”creative” modifications for us to be efficient walkers and runners.

In anthropological circles, this muscle’s strength and flexibility may have been directly related to our significant neurological growth as a species – for as we stood tall, able to see over the grassy plains, there was more to sense, think, and plan, enabling us to secure the title of “Dominant Life” on our little marble we call Earth.

But back to the hip flexor…you may imagine by the name that it flexes the hip. Correct! However, it also externally rotates the hip, even if just a little. If you didn’t know, now you know!

The Cascade of Complications

Sitting is a double-edged sword in human life. Our usual chair/couch sitting position would be described as hip flexion, external hip rotation (for most), and some mild horizontal hip abduction, yes? Well, this is where a whole lot of low back and hip issues come from.

Step 1: Human sits for a long time, develops adhesions and increased muscle tone in these positions. (Read: muscle tension)

Step 2: Human tries to stand, or walk, or run…unsuccessfully.

What happens here is our tension system gets thrown off and tuned more towards sitting, so as we stand the psoas group has to lengthen…this doesn’t happen without a fight. Usually, there are significant adhesions along the muscle, tendon, or even joint that limit this motion.

Ultimately you’ll notice a decreased ability for your sedentary client to extend their leg past neutral standing posture (more than 0 degrees, with normal being 15 degrees), which ends up looking like a hunched shuffle. Not great when you’re trying to promote quality movement.

The other thing to consider is a closed-chain versus open-chain thing. If my psoas group was tight for whatever reason and I was floating in space, I’d passively end up in somewhat of a fetal position, with my knees tucking up towards me. However, we’re not floating in space, and when our feet are planted on terra firma, the psoas just stays pulled taut but not in at optimal length-tension relationship.

Since the force of gravity prevents our muscles from pulling the legs toward us while standing, they end up pulling us towards our legs. The low back, which is already predisposed to have a slight curve, ends up getting yanked forward into excessive lordosis when the legs attempt to move into an extended or even neutral position (anything that’s not flexion), and the low back muscles and joints end up crunching into each other.

This has a bad effect on our bodies, causing a cascade of compensation and tightness often leading to pain. Ever tried to have a client lay flat supine, and they just have to keep their knees bent because of low back or hip pain?

There’s your explanation: Psoas is so tight it’s pulling the back forward into further extension (lordosis) and causing a kerfuffle (or however you spell that). It’s rare that psoas is the only issue. All of the other hip flexors (TFL, glute minimus, anterior adductors, etc) are probably tight as well, especially for sedentary individuals. If someone has low back pain, quadratus lumborum may be seizing up as well.

Much like crocodile jaws, the hip flexor muscles become synergistically dominant over the extensors, leading to strained and weak glutes, hamstrings, tight and tender low backs, poor ambulation, slow running speeds…the list goes on.

How to Make Happy Hips

Does your client have short psoas muscles? Here’s a quick test to find out: Have your client lie in his or her back with straight legs and pull one knee into the chest tightly. Watch the other leg closely. Does it pop off the floor a bit (or a lot?) Like it also wants toa hug into the chest?

That’s a tight psoas! And a chronically short muscle is likely to have adhesions.

If we know tightness and adhesions he are problems, we need to implement proper mobilization procedures to healthy-up those hips. I personally suggest laying on a lacrosse ball around the front side of the hip while performing active psoas and quad stretches. A skilled manual therapist can also help to release the deep belly of the psoas (…deep in the belly). Best not to dig around in there as there are too many sensitive structures surrounding the psoas.

Be sure to utilize proper belly breathing on core exercises to tease out adhesions, practice hip extension exercises like a glute bridge (slow and controlled!). Studies indicate that low back pain is more likely to be associated with loss of internal hip rotation. I.e., they can’t perform an optimal degree of internal hip rotation.

If you’re not sure what you’re working with, performing an overhead squat assessment and looking for the cues of knees bowing in (excessive internal rotation) or knees bowing out (excessive external rotation) will help clear things up. If those knees flare out, then working on internal rotation of the hip (banded or otherwise) is a great idea.

There are a thousand and one ways to address a tight muscle, and yours will certainly differ from mine, but now that you know how important proper balance for hip flexion tension in the human body is, I hope this little blog will inspire you to go forth and discover what works for you and your client populations!

Cheers,

Dr. Patrick

Dr. Patrick K. Silva is a Board Certified and Licensed Doctor of Chiropractic with a focus on Sports Rehab, practicing in the beautiful US Pacific Northwest. Building on his preceptorship with the Seahawks' chiropractor (Dr. Jim Kurtz) in 2016, Dr. Patrick has designed his practice around the numerous soft tissue techniques, movement systems, and rehabilitative paradigms that modern sports science has to offer. Dr. Patrick is also a Certified Office Ergonomics Evaluator and Certified Professional Trainer. In his spare time, Dr. Patrick enjoys DIY projects and stays active practicing martial arts, soccer, dodgeball, parkour, and gaming.