Understanding the attachments and function of the erector spinae group can help shed light on some typical compensation patterns and postural dysfunction like hyperkyphosis or excessive lordosis often seen in our clients. With low back pain afflicting an estimated 50% of the population (at least), becoming intimately acquainted with the muscles of the back will provide personal trainers with more information to program corrective exercise and more effective fitness programming.

The intermediate intrinsic musculature of the back is comprised of the three erector spinae muscles, which collectively work to bilaterally extend, and unilaterally rotate and laterally flex the spine. They are the middle layer of intrinsic back muscles overlaying the deep intrinsic layer and beneath the most superficial layer located in the upper thoracic and cervical portions of the vertebral column.

The Muscles of the Back Categorized

Starting broadly, all the muscles of the back can be categorized into one of three layers:

- Superficial (the global movers of the shoulder and scapulae such as the lats, trapezius and rhomboids)

- Intermediate (the thoracic cage muscles that assist in breathing: Serratus posterior superior and inferior)

- Deep (the intrinsic muscles that are associated with the vertebral column)

Those deep, intrinsic muscles are further broken down into those same three categories:

- Superficial Intrinsic (the spinotransversales): The top layer of intrinsic muscles that extend and rotate the cervical spine.

- Intermediate Intrinsic (the erector spinae): The middle layer that extends from the lumbosacral fascia up to the cranium and primarily extend the spine, rotate and laterally flex it. (The subject of this blog)

- Deep Intrinsic (the transverospinales): The deepest layer of tiny local stabilizer muscles that primarily control the segmental motions of the spine.

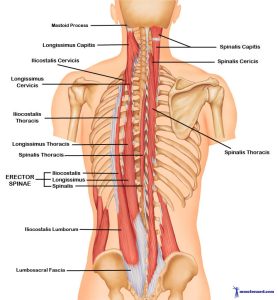

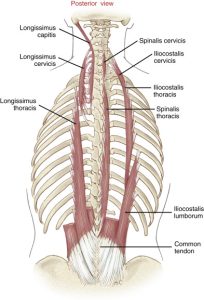

The Three Muscle Groups of Erector Spinae

The erector spinae collectively are the muscles that support the spine, keep it upright and stable, and also extend and rotate.  The easiest place to start is by recognizing the three main groups, where they are located and what actions they each perform. Then those groups get further divided into specific functions and locations on along the spine.

The easiest place to start is by recognizing the three main groups, where they are located and what actions they each perform. Then those groups get further divided into specific functions and locations on along the spine.

The Iliocostalis: This is the outermost group running from the common tendon (in the lumbosacral fascia which invests in the sacrum) all the way to the upper ribs.

You can remember this group by recalling the intercostals as well: the muscles that help move the ribs when breathing. The iliocostalis muscle is furthest from the spine and attaches to the ribs along the way.

Bilaterally, the iliocostalis group extends the spine. Unilaterally, it assists with lateral flexion. It is separated into three segments associated with each segment of the spine:

- Lumborus (starting at the common tendon and fanning slightly outwards to insert into ribs 12-6)

- Thoracis (inserting from just beneath the lumborus attachments on ribs 12-6 upwards into ribs 6-1)

- Cervicis (inserting from just beneath the thoracis attachments on ribs 3-7 upwards into the spinal processes of C4-C6)

The Longissimus: This group is in the middle. It is the loooooongest muscle supporting the spine (wink, wink), and like iliocostalis, bilaterally extends the spine and unilaterally laterally flexes it. It inserts from the common tendon just medial to the iliocostalis attachment and extends all the way up to the base of the skull. Despite the fact that this muscle runs past the lumbar spine, it does not have a distinguished “lumborus” section like iliocostalis group. It does still have three segments:

- Thoracis (inserting from common tendon up into the transverse processes of T12-T1)

- Cervicis (inserting from transverse processes of T4-T1 through the processes C6-C2)

- Capitis (inserting from transverse processes of T5-T1 and facet joints of C7-C3 to the mastoid process of the temporal bone, i.e. the skull)

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/erector-spinae-muscles

The Spinalis: As it sounds, this muscle runs right along the spine. Like Longissimus, it runs from the common tendon up to the base of the skull (but is just a tad shorter). And also like longissimus, it may pass over the lumbar region but it does not have a designated “lumborus” section either. In fact, just think of this one as the thinner accompaniment to longissimus, whose job is to help extend the spine but also support its individual segments.

It functions unilaterally to laterally flex the vertrabral column, and bilaterally to extend the verbral column and head.

- Spinalis capitis (inserting from the spinous processes of C1, C3 and C4 into nuchal ligament).

- Spinalis cervicis (inserting from the spinous processes of C4-C7 into the spinous processes of C3-C5).

- Spinalis thoracis (inserting from the spinous processes of T7-L1 into the spinous processes of T1-T6).

Training Considerations for Erector Spinae

These muscles tend to be under stress and tension consequential to a sedentary lifestyle translating into postural distortion from sitting. Someone slouched forward and in a posterior pelvic tilt will have long and weakened erector spinae, concurrent with a weak core. This client may have an excessive trunk flexion while performing a modified overhead squat assessment with hands on hips.

You could also have the client attempt to touch his or her toes with straight knees. If the middle and low back rounds excessively and the floor can’t be reached, the excessive spinal flexion needs to be balanced.

This can often translate into a feeling of “tightness” but in this case, stretching would be contraindicated; strengthening this muscle group and deep core muscles will help alleviate discomfort and pain, while also training the body to hold a more ergonomic posture while sitting or standing for extended periods.

Programming bird-dogs and dead bug exercises thoughtfully is the recommended approach. While it is tempting to assign back extension motions, this is likely too much load for someone with weak and lengthened extensors. A more conservative and steady approach is all that is needed to start.

Conversely, any individual presenting with anterior pelvic tilt may suffer from short overactive erector spinae muscles concurrently with quadratus lumborum, and possibly suffer from low back pain. When this client attempts to touch their toes you may note that the back stays flat while the cervical spine extends, indicating a short and tight erector spinae group.

This person should avoid hyperextension exercises and may benefit from static release with a foam roller of the thoracic erectors. (Avoid attempting to roll the lumbar region which may exacerbate symptoms). Strengthening the rectus abdominus and hamstrings, while stretching the hip flexors is one corrective approach.

Have you noticed your clients complaining of back pain or appear to have tight spinal erectors? In what other ways might it be important to keep this muscle group in mind when training?

References

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/erector-spinae-muscles

NFPT Publisher Michele G Rogers, MA, NFPT-CPT and EBFA Barefoot Training Specialist manages and coordinates educational blogs and social media content for NFPT, as well as NFPT exam development. She’s been a personal trainer and health coach for over 20 years fueled by a lifetime passion for all things health and fitness. Her mission is to raise kinesthetic awareness and nurture a mind-body connection, helping people achieve a higher state of health and wellness. After battling and conquering chronic back pain and becoming a parent, Michele aims her training approach to emphasize fluidity of movement, corrective exercise, and pain resolution. She holds a master’s degree in Applied Health Psychology from Northern Arizona University. Follow Michele on Instagram.