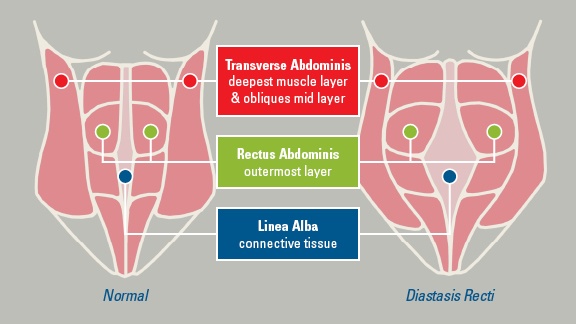

Diastasis Recti is a condition that can affect infants and pregnant women, but personal trainers should be aware that they aren’t the only ones that can be afflicted. Rectus abdominus (RA) requires recruitment of the transverse abdominis (TVA) to sustain abdominal strength in order to prevent separation of the linea alba, the connective tissue that binds the center of RA. This separation of the linea alba is a diastasis and can occur in varying degrees.

RA muscular development is a great show highlight, but be careful in equating that development to genuine core strength. Why? Because for the most part in developing the rectus abdominis one may be off-setting development of the TVA sheath of muscle beneath. The TVA acts as a corset that supports the lumbar spine.

Without equal attention to the TVA, the linea alba will (see picture below) soon begin to weaken causing the medial line of the left and right rectus abdominis to separate, causing pain and sometimes protrusion of tissue between the muscle walls.

http://momsrunthistown.com/blog/diastasis-recti-yoga-and-you/

What is Diastasis Recti?

The gap between the left and right rectus abdominis muscles is called Diastasis Recti. [1,2] (The condition, however, has no associated morbidity or mortality and should be differentiated from an epigastric hernia or incision hernia, which can be ruled out using ultrasound[2].)

“The distance between the right and left rectus abdominis muscles is created by the stretching of the linea alba, a connective collagen sheath created by the aponeurosis insertions of the transverse abdominis, internal oblique, and external oblique.” [3]

Who’s at Risk for Diastasis Recti?

It’s common for babies to be born with DR, especially premature babies. Usually, no intervention is required and the gap will close gradually as the baby grows.

Later in life, the risk of developing Diastasis Recti increases for adults who:

- Are overweight in the abdominal area

- Lift heavy weights incorrectly

- Perform excessive and inappropriate abdominal muscle exercises

- Are pregnant

Women and DR

“Women are more susceptible to Diastasis Recti when over the age of 35, high birth weight of the delivered baby, multiple birth pregnancy, and multiple pregnancies. Additional causes can be attributed to excessive abdominal exercises after the first trimester of pregnancy.”[4]

The separation known as DR usually runs from the xiphoid process to the umbilicus resulting in a ridge running down the midline of the abdomen. It becomes more prominent with straining and may disappear when the abdominal muscles are relaxed. The medial borders of the right and left halves of the rectus abdominis muscle can be palpated during contraction.

Diastasis can be considered a symptom of chronic core weakness. Just like core weakness can cause back pains, disc herniations or lead to knee, ankle, or neck pains, it can also lead to diastasis. This happens when the core’s inner unit is not effectively transferring forces–when it is not regulating intra-abdominal pressure effectively.

If an excess of pressure is consistently forced into the tendinous linea alba sheath rather than balancing synergistically throughout the abdominal muscles, the forces may be great enough over time to cause severe stretching. In theory, this can happen to anyone, but especially a pregnant mother who has a fast-growing uterus that requires her core to adapt relatively quickly, potentially stretching the connective tissue.

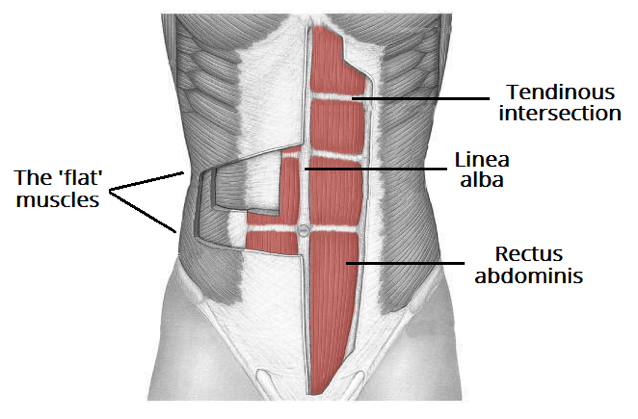

Image: Anterior sectional view of the abdominal cavity, revealing the linea alba tendinous sheath.

There are two types of pregnant moms who are likely to incur a diastasis stretch of the linea alba. Most common is the woman who is a “core amnesiac.” This means that the woman has very little core awareness before pregnancy (like most of our clients when newly starting with us). The under-activation of the core often means that the diaphragm, pelvic floor, and TVA do not function with the appropriate tension at the appropriate times, leaving the belly to be overly relaxed. Once pregnant, that lack of core awareness simply perpetuates, and the relaxed belly muscles relax farther than they might otherwise. The vast majority of prenatal clients will fall into this category.

The other common type of diastasis-risk prenatal client is the opposite: instead of a relaxed core, she has an over-active core. This is more likely to be a fitness enthusiast and sometimes those who have taken their love of abdominal exercises to a level that may no longer be serving them (Pilates, for example). In this case, your client may have learned to constantly tighten her stomach, and will often be proud of her “tight” abs.

Tight abs are great on the occasions that they should be contracted, but not necessarily all the time. The diastasis occurs when this tight TVA is trying to hold back a uterus for nine months. The uterus will win. As the uterus grows outward, it can force a stretching of the linea alba sheath, and now this “super-fit” woman is surprised to find out that she has diastasis.

Pregnancy can often exacerbate previous symptoms or reveal musculoskeletal challenges that are likely to occur years later. This is where misalignments such as pelvic girdle pain, sacroiliac joint dysfunctions, symphysis pubis dysfunctions, sciatica, disc herniations, piriformis syndrome, and many other challenges can arise. They are all generally symptoms of the “stress” of pregnancy being placed atop an already faulty musculoskeletal alignment.

As a solution that will last a lifetime, have no side effects, and require no surgery, Fit For Birth teaches the Core Breathing Belly Pump (CBBP)™. It is defined as, “the rhythmic inhaling and exhaling that maintains activations of the diaphragm, TVA, and pelvic floor (PF) muscles to dynamically maintain intra-abdominal pressure so that the core may assist in stabilizing, accelerating, and decelerating any exercise.”

Effective prenatal coaching emphasizes a balance between core amnesia and the excessive all-day holding of a super-tight TVA. More specifically, it can be thought of as coaching the natural rhythmic breathing cycle of concentric TVA contraction (on the exhale) followed by an eccentric TVA contraction (on the inhale).

The natural rhythmic cycle should be predominantly powered by the diaphragm all day long, with more activation and tension during the times that are necessary (like during exercise). Naturally, the core tension would be less aggressive during easier activities of daily life, but still needs to be coached into greater activation in most clients!

In many ways, CBBP™ is similar to other diastasis prevention and treatment techniques, like the Tupler Technique®, but is also being regarded as a simple foundational principle because it’s based upon something your clients do 20-25,000 times every day: breathing.

The most important aspect of the CBBP™ is that your client can perform a proper diaphragmatic breath, which is unfortunately difficult for the vast majority of pregnant (or non-pregnant) clients. In brief, the first two-thirds of a “deep inhale” should notably enter the ribs, belly, and back first. It is then considered biomechanically correct for the chest and shoulders to rise in the final third of the inhale of a “deep breath,” but not before. After asking just a handful of clients to “take a deep breath,” you will start to see patterns and build your familiarity and expertise in coaching.

If the diaphragmatic breath is not optimal, core activation techniques like the CBBP will not likely be enough to prevent core dysfunction symptoms like diastasis recti. In the human body, the diaphragm muscle is top of the totem pole. And in most of your clients (often nine out of ten) it will literally need to be trained, like lifting weights.

Helping your clients create a balance of diaphragmatic breathing and core-TVA activation before, during, and after pregnancy will help them have optimal core strength while decreasing their chance of having abdominal separation.

[sc name=”masterfitness” ][/sc]

Diastasis Recti and Personal Training Clients

Diastasis Recti is a symptom of excessive and unsupported intra-abdominal pressure, the same state that creates other pelvic and abdominal problems including hernia and prolapse. Intra-abdominal pressure increases when performing exercises such as squats, deadlifts, planks, and the like. Any resistance exercise when the Valsalva maneuver (forcibly exhaling while keeping the mouth and nose closed) is employed (which keeps the chest and shoulders firm and rigid, bringing greater support to the arms) will cause unnecessary intra-abdominal pressure.

Correct breathing has to be a conscious effort in weight-lifting sports. If breathing is not performed correctly during weight training it will lead to potentially serious problems such as dangerous spikes in one’s blood pressure. Improper breathing may lead to core weakness and improper musculature contractions, and as previously mentioned will lead to stretching/tearing of the linea alba.

When DR happens to weight lifters there should be an integrated program designed to re-align, re-connect and then strengthen the entire core musculature, rather than be addressed in isolation (and rather than focussing only on ‘closing the gap).

The following movements are contraindicated with Diastasis Recti:

- Any exercise that causes the abdominal wall to bulge out.

- Certain yoga poses that stretch the abdominals, e.g. the cow pose, all backbends, and belly breathing.

- Pilates movements such as spinal flexion, head float, double leg extension.

- Movements where the upper body twists, causing one hand to touch the foot while the other hand extends upward.

- Using an exercise ball to lie backward.

- Flexing the upper spine off the floor against gravity.

- Abdominal crunches.

To help build abdominal strength, (which may or may not help reduce the size of DR) the following is suggested [5]

- Core contraction – In a seated position, place both hands on abdominal muscles. Take small controlled breaths. Slowly contract the deep abdominal muscles by pulling them straight back towards the spine, and away from the waistband. Hold the contraction for 30 seconds, while maintaining the controlled breathing. Complete 10 repetitions.[5]

- Seated squeeze – Again in a seated position, place one hand above the belly button, and the other below the belly button. With controlled breaths, with a mid-way starting point, pull the abdominals back toward the spine, hold for 2 seconds, and return to the mid-way point. Complete 100 repetitions.[5]

- Head lift – In a lying down position, knees bent at 90° angle, feet flat, slowly lift the head, chin toward your chest, (concentrate on isolation of the abdominals to prevent hip-flexors from being engaged),[6] slowly contract abdominals toward floor, hold for two seconds, lower head to starting position for 2 seconds. Complete 10 repetitions.[5]

- Upright push-up – A standup pushup against the wall, with feet together arms-length away from wall, place hands flat against the wall, contract abdominal muscles toward spine, lean body towards wall, with elbows bent downward close to body, pull abdominal muscles in further, with controlled breathing. Release muscles as you push back to starting position. Complete 20 repetitions.[5]

- Squat against the wall – Also known as a seated squat, stand with back against the wall, feet out in front of body, slowly lower body to a seated position so knees are bent at a 90° angle, contracting abs toward spine as you raise body back to standing position. Optionally, this exercise can also be done using an exercise ball placed against the wall and your lower back. Complete 20 Repetitions.[5]

- Squat with squeeze – A variation to the “Squat against the wall” is to place a small resistance ball between the knees, and squeeze the ball as you lower your body to the seated position. Complete 20 repetitions.”[5]

All corrective exercises should be approached by pulling in the abdominal muscles rather than pushing them outward. A favorite exercise among strength trainers to correct DR is:

- Lie on your back, knees pulled in allowing feet to be flat on the floor

- Grab the left side of the RA with the right hand and the right RA with the left hand.

- Perform a posterior pelvic tilt

- While the lower back is flexed to touch the floor, perform a crunch without lifting the shoulders off the floor and pull both sides of the rectus abdominis together while breathing out.

- Relax and breathe in, releasing the spine

- Repeat the crunch, again focusing on pulling both halves of the rectus abdominis together.

*Consultation with a professional physiotherapist is recommended for correct exercise routines.

In effect, the strengthening must come from the inside out; i.e. the TVA, the inner, deepest abdominal muscle. The typical crunches, sit-ups, bicycle crunches do not effectively engage your TVA.

Pushing the abdominal cavity outward will not develop the TVA. Rather, in addition to pushing your abdominal cavity outward which focuses only on the rectus abdominus there also needs to be a pulling the abdomen inward toward the spine which will develop the TVA muscle sheath, preventing the separation of the linea alba, i.e. Diastasis Recti.

[sc name=”core” ][/sc]

References

1 Benjamin, D.R.; Van de Water, A.T.M; Peiris, C.L. (March 2014). Effects of exercise on diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle in the antenatal and postnatal periods: a systematic review. Physiotherapy 100 (1).

2 Norton, Jeffrey A. (2003). Essential practice of surgery: basic science and clinical evidence. Berlin: Springer. p. 350. ISBN 0-387-95510-0.

3 Brauman, Daniel (November 2008). “Diastasis Recti: Clinical Anatomy”. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 122 (5).

4 Harms, M.D., Roger W. ”.Why do abdominal muscles sometimes separate during pregnancy?

5 Liao, Sharon (February 2012). “15 minutes and you’re done: crunch-free abs”. Real Simple (Time Inc.) 13 (2).

6 Engelhardt, Laura (1988). “Comparison of two abdominal exercises on the reduction of the diastasis recti abdominis of postpartum women”. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. UMI Dissertations Publishing. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

Dr. Brancato’s cumulative experience in nutrition, alternative medicine, chemistry, toxicology, physiology directed him to holistic approaches in human physiology to correct system imbalances. He maintains his professional certifications as a Naturopath from the American Naturopathic Medical Certification and Accreditation Board; the National Federation of Professional Trainers; Black belts in Kick Boxing and Kenpo.