Personal trainers are well-versed in working muscles, but what about the tendons and ligaments that hold the muscles to each other and to bone? These structures are just as important to consider and program for when training a client; neglecting them can lead to injury. What is connective tissue training, why is it important, and how should fitness coaches approach it?

The Weakest Link

You’re only as strong as your weakest link. It is an old cliché; but to someone who trains hard, it holds true.

Think about it: What is your weakest link? Is it calves? Glutes? Traps?

Before you think of weak links in terms of muscle, consider this: If you exhaust a muscle, you can wait a few days or so and then train it to the max again. Even if you tear a muscle, you can train around it while you wait a few weeks for it to heal (ill-advised, but possible).

But, if you’ve got a weak or injured tendon or ligament, then you’ve really got problems. Connective tissue builds and heals slowly. A partial tear can take four or more months to heal; sometimes it never does. A complete tear will undoubtedly need surgery. Then you are looking at more than nine months of healing, plus atrophy in surrounding muscles because they can’t be worked while adjacent connective tissue is recuperating from going under the knife.

In many obvious ways – and some which are not so obvious – your connective tissue is your weakest link. After all, muscle strength is limited by the ability of the tendon to handle the force generated by the muscle, and the muscle system is affected by the strength of the ligaments to stabilize the joints involved in the lift.

That’s why building the muscles without conditioning the connective tissue leaves you open to injury, weakness, and pains, which can turn chronic, limiting your range of motion. Common sense dictates a simple solution: Make the tendons and ligaments stronger. The question is, how?

Understanding Connective Tissue

Like any aspect of resistance training, the answer requires knowledge of the basics. Without understanding well how the body works, it is difficult to program optimally and achieve training goals. So, let’s start with the most basic question: What are tendons and ligaments and how do they get stronger?

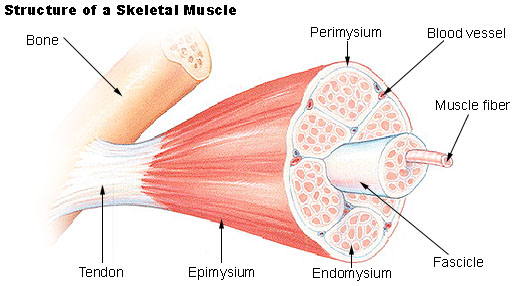

Every muscle has a tendon on each end that attaches the muscles to the bone. Tendons are made of thick, rubbery white tissue. Any kind of skeletal movement, from walking to lifting weights, happens because the muscle contracts, pulls on the tendon, which in turn, pulls on the bone and moves it.

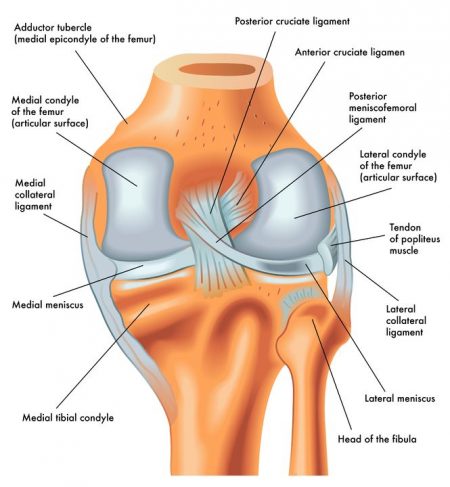

Ligaments are also attachment tissues; they connect one bone to another. They hold the joints together. Ligaments are thinner and less elastic than tendons. They also are white.

The whiteness of these tissues explain the major reason for their slowness to grow and/or heal: unlike the red, juicy muscle tissue, tendons and ligaments have very little blood supply. Even bones have more blood flow than connective tissue, which is why a broken bone can heal in four to six weeks, versus nine months for tendons and ligaments.

The whiteness of these tissues explain the major reason for their slowness to grow and/or heal: unlike the red, juicy muscle tissue, tendons and ligaments have very little blood supply. Even bones have more blood flow than connective tissue, which is why a broken bone can heal in four to six weeks, versus nine months for tendons and ligaments.

This is because the bloodstream supplies the oxygen and nutrients needed for growth, repair, and function. It flushes out waste products and toxins and carries them away. Getting the maximum possible blood supply into these tissues is a good idea.

Two Processes to Building Up the White Connective Tissue

Two kinds of vascularization are important in building the connective tissue. You may be familiar with one of them already: The Pump. When a muscle is contracted over and over again, it uses a lot of energy. In turn, it requires large and immediate amounts of oxygen and nutrients. Using energy also produces waste products that need to be quickly removed in order for the muscle to continue working.

The body responds by sending a greater supply of blood surging through the blood vessels of the muscle, to feed it and flush it. You feel this as heat and swelling. But there’s also another response and adaptation process known as capillarization. As blood vessels of the muscle in question grow as they continue to be “pumped”, new capillaries begin to branch out and furnish even more blood to the area.

This increased supply of blood supply allows the muscle to grow in response to training. The increased muscle mass creates the need for more blood supply, and the two adaptive processes complement each other right up to the limit of a person’s genetic potential, or perhaps more accurately, his or her level of dedication up to that point.

The vessels of that muscle will get bigger as you continue pumping it; new capillaries will start to branch out so that even more blood can be sent to the muscle. This greater blood supply allows the muscle to grow in response to training. The increased muscle mass creates the need for more blood supply, and the two adaptive processes complement each other right up to the limit of your genetic potential – or discipline, whichever comes first.

Although ligaments and tendons don’t have the capacity to build a large network of blood vessels, you can still manipulate the adaptation process to push them to their greatest possible development.

Vascularized connective tissue is far less likely to tear or rupture under extreme stress. Studies show that the loss of elasticity, which is the major sign of aging in white tissue, can be delayed and/or minimized by proper conditioning. In addition, if a maximally vascularized tendon or ligament is injured, it will heal a lot better, and full function will return much faster than less conditioned white tissue.

Connective Tissue Training Program

Proper Warm-Up and Prep

The first part of any tendon/ligament conditioning program should begin with a proper warm-up. It’s essential that stretching comes after a warm-up or workout. You need to increase the core temperature of the body for an effective warm-up, and before attempting to lengthen muscle or connective tissue. Whether this is achieved via a brisk walk, 10 minutes on the stationary bike, or dynamic bodyweight movements, you have to get the body’s core temperature up before to make tissue more pliable.

You’re warmed up sufficiently if you notice a light sweat, because that shows that your temperature has come up and the body is trying to cool itself.

Strength Training Connective Tissue

Although it runs below the surface, strong connective tissue has a marked effect on what does show, i.e., musculature. A loss of elasticity, which is the major sign of aging in white tissue, can be delayed and/or reduced by proper conditioning, some studies have shown. In addition, if a maximally vascularized tendon or ligament is injured, it will heal better, and full function will return much more rapidly than it would in less conditioned white tissue.

While the work aimed at the muscles will provide some degree of conditioning for the tendons and ligaments, it will be less efficient than a workout designed with the connective tissues in mind. For improving connective tissue, flexion and a high number of reps with minimal resistance should be involved. This is because as the joint is stressed during exercise, the ligament will respond to being stretched. The more it is stretched, the more it will respond by adding cells and collagen, effectively strengthening the joint.

Paulos explains: “As you exercise and stress the joint, the ligament will respond to being stretched. And the more it’s stretched, the more it will respond by laying down cells and collagen, making it stronger.”

When you strengthen a ligament, you actually add to its blood supply. In order for the ligament to get larger, it has to have more blood. The blood is interspersed between the collagen fibers. When a muscle is contracted repetitively, it automatically vascularizes the tendons – within their limits.

When you repetitively contract a muscle, it automatically vascularizes the tendons within its limits; two types of workout should be integrated into your program:

Workout routines designed to improve flexibility and/or definition to muscle groups should be interspersed with overloading types of routines that load the muscle beyond its capacity. Low weights with lots of reps (20-30) will stretch the muscle and stimulate blood flow. But unless you overload the muscle, it won’t hypertrophy and blood vessels probably won’t increase in size or number. You have to overload tissue to get it to respond by laying down more tissue, whether it is blood vessels, ligaments, or bulk.

Cool Down

Integral to connective tissue training, is ending a workout with a proper cool-down is as important as beginning it with a proper warm-up: It is a must. Exposure to cold water (in the range of 60-70 degrees Fahrenheit) can help restore muscles more quickly than heat and can help heal microtrauma. Once you’ve taken time off to rest an injury, proceed with stretching, negatives, and a few low-weight/high-rep workouts. While it might mean losing a few weeks out of a cycle, it is still preferable to losing even more months and working one’s way back from surgery to repair injured tendons or ligaments.

Types of Connective Tissue Injury

Tears

Even strong tissues can be injured if their owner doesn’t know the mechanisms of trauma. The most traumatic damage, of course, is a tear. The most common kinds of tears are usually ballistic tears which happen when a person changes direction in a hurry or makes a sudden motion in a hurry, or makes a sudden motion like in Olympic lifts or stop-and-go sports, like basketball.

Strength is a crucial factor in preventing the tissue from tearing in two due to injury. It is preferable for the tissue to tear from the bone than to tear in two (also making surgery easier because otherwise, you can’t get a good suture hold, but a surgeon can more easily repair it if it has a chunk of bone attached to it).

Because connective tissue builds and heals much more slowly than does muscle, even a partial tear can take months to heal; in some cases, it may never heal completely. A complete tear typically means surgery, and from 6-9 months to heal. This also leads to atrophy in adjacent muscle tissue, since they can’t be worked during the recovery period.

Microtrauma

Tears are perhaps the most noticeable type of connective tissue injury, but there is a more insidious type of injury that can show up when least expected. Such are microtraumas, which as the name suggests, involve microscopic injuries to tissue and often result from repeated overuse and not enough recuperation time.

A creeping microtrauma that occurs in a ligament or tendon often means tissue is being stretched excessively. For example, if a ligament stretches more than 10-15% beyond its normal length, it will tear. However, if it stretches 8%, it will typically incur a microtear, or microtrauma. If the ligament is repeatedly stretched by 8%, it can weaken to the point where it takes less force than it otherwise would for it to be ruptured.

Fortunately, microtrauma can be prevented by taking rest periods in between sets and in between workouts. If the body is sufficiently rested, microtrauma can be healed by the vasculature. Microtrauma can also be caused by improper form while lifting. Proper form has developed as a way of balancing the body biomechanically under a heavy load, which is why it is so important to keep in mind.

Some signs of microtrauma include:

- soreness in one muscle area when other muscles used in the workout have already recuperated;

- an unusual feeling of instability, such as a buckling sensation or “popping” feeling in the joint;

- a feeling of a muscle twitching or trembling after doing a heavy set;

- pain after a workout that repeatedly occurs only at a certain point in the range of motion.

If one or more of these signs are noticed, it’s important to take them seriously and allow for some recuperative downtime.

Connective Tissue Rehab (Yes, Yes, Yes)

Among bodybuilders, tendons tended to be injured far more often than ligaments. If a tendon is injured seriously enough to interfere with training, but not seriously enough to require medical care, proper rehab is necessary. It is essential to take time to rehabilitate a soft tissue injury, no matter how minor it might seem.

“Working through the pain” carries the risk of letting temporary inflammation lead to chronic inflammation, known as tendinitis. In such an instance, the best way to deal with a tendon-related injury is to rest it until the acute inflammation phase is past. When resuming training, do so gradually. If there is pain during the workout, but it subsides, it’s likely that things are fine. However, if pain persists two hours later, it is likely due to overexertion and the routine should be modified accordingly.

In conclusion, the best way to prevent injury to tendons and ligaments and to program connective tissue training is to include both high-rep training and hypertrophy training. The combination of these two approaches will pump more blood into these tissues while also allowing the effects of muscle hypertrophy to increase the vascular structures flowing toward the connective tissue; increased blood flow to tissue helps to flush metabolites and keep the tissue warm and pliable ultimately reducing the risk of injury.

[sc name=”functional” ][/sc]

References

1. Enoka, Roger M. Neuromechanical basis of kinesiology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1994

2. Kannus, P. “Structure of the tendon connective tissue.” Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 10.6 (2000): 312-320.

3. The National Federation of Professional Trainers. Sports Nutrition Manual. 2nd Ed. Lafayette, IN: NFPT, 2006.

4. Tipton, Charles, M., Vailas, Arthur C.,, and Matthews, Ronald D. “Experimental studies on the influences of physical activity on ligaments, tendons, and joints: a brief review.” Acta Medica Scandinavica 220.S711 (1986): 157-168.