Having a solid grasp on how to use periodization programming with personal training clients may be the difference between successfully advancing in training while preventing injury and someone who just “works out” a lot, failing to meet goals and perhaps getting injured in the process.

We as trainers should all have a solid grasp on which rep ranges are ideal to stimulate a specific training response and how to progress from one phase to another (i.e., from muscular endurance to max strength). But, how many of us are efficiently programming and tracking training adaptations, while also planning recovery cycles?

I’ll be the first to admit, I’ve been pretty terrible about recording these cycles. I have believed for a long time that I have developed such a knack for my craft that I have a running tabulation of my clients’ strength gains and weight capacities in the “cloud” of my conscious mind. While it’s true, I probably pretty accurately can recall the last session’s sets, reps and weight lifted, and I am constantly progressing them, I don’t remember what those factors were a year ago and how strictly I have been following the principle of general adaptation.

This has been a failure on my part to properly track my clients’ progress and missed opportunities to assess and re-assess goal achievements. I’m turning over a new leaf, and if you’re a fitness professional with a tracking track record that sounds like mine, I hope I can convince you to do the same.

Periodization Defined

Periodization is the systematic cycling of various, progressive aspects of training (such as intensity, volume, and specificity) in planned time blocks to improve outcomes and reduce overtraining effects. It is an approach that can be used for any sport, including (and especially) strength training.

There are three main cycles that comprise periodization: a macrocycle, a mesocycle, and a microcycle.

A macrocycle is the period of time that encompasses the entire training period, but is usually limited to no longer than one year. The macrocycle is further broken down into 3 or 4 shorter blocks: a mesocycle.

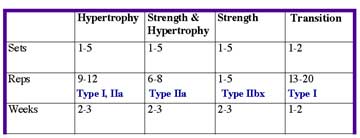

A mesocycle can be a few weeks to a few months long and can be further broken down into specific sport phases such as preparation, competition, peaking, and transition phases. For personal training clients, you might break down a macrocycle into four main mesocycles: muscular endurance, hypertrophy, strength, and transition.

The transition cycle is intended to give the body a bit of a break with reduced intensity and volume before preparing for the next cycle, also known as deloading.

Each one of those mesocycles might last 4-6 weeks and could be further broken down into weekly microcycles. This is just one example

A microcycle is usually—you guessed it—one week long. And if you’re programming for a client who might train with you one to three times a week and maybe a few times independently, then you may have to program up to 5 or 6 workouts to make up that microcycle.

Including recovery and/or tapering periods is an important aspect of periodization to assist in soft tissue recovery and adequate time and space for adaptations to occur, especially during higher-intensity strength and power phases of training.

Types of Periodization

- A linear, or step-wise, periodization program for a general fitness or weight loss client just starting out with resistance training, as suggested above, will begin with higher volume lower intensity stimuli and progress towards lower volume and higher intensity stimuli. This program can be repeated several times, especially for those newer to fitness.

- An undulating or non-linear periodization program will vary the volume and intensity applications throughout the mesocycle in a seemingly random, but purposeful way. The idea here is to couple two goals concurrently, such as strength and hypertrophy, or endurance and power. This approach may be ideal for someone training for two or more years and who has reached a plateau or is ready for an increased challenge.

- A block periodization is appropriate for serious and elite athletes. The mesocycle blocks are designed to specifically develop and nurture the skill set needed for the sport or for a solitary goal. The specific blocks are defined as accumulation (50-75% intensity), transmutation (75-90% intensity), and realization (90%> intensity).

- An overreaching period is a brief one to two-week increase in volume and/or intensity before returning to normal training or one of the above periodization programs. The purpose is to truly shock the system and overload to produce a greater effect during a subsequent taper or rest period. This approach is appropriate for a seasoned athlete or lifter.

[sc name=”resistance” ]

How Long Should Each Cycle Be?

Here is where your expertise as a fitness professional and getting to know your client will come into play. Starting with a beginner client, the first cycle will generally be the longest as the client adjusts to resistance training, makes neural adaptations, and is laying each brick of a fitness foundation. After that, plan the length of each mesocycle according to the client’s specific goals.

The first mesocycle of a beginner weight loss or general fitness client may have to start with very light or no weight movements in a low rep range to establish mitochondrial performance. You might do a total body circuit of compound movements with a goal of failing at 12 reps for the first few weeks. The mitochondrial “re-education” will have occurred when the client can perform the same number of reps for each set without failing too early. Expect this to take three to six weeks.

As long as the overload principle is being applied and you are progressing the client in each phase, successfully achieving the set weight, volume, and intensity as planned, then expect each phase or mesocycle to last tw0 to four weeks before moving on to the next, with the exception of a transition phase that can be one to two.

Don’t forget to implement a sound nutritional periodization program to accompany the training periodization you have designed.

[sc name=”masterfitness” ][/sc]

References

- Frankel, C.C. & Kravitz, L. (2000). Periodization: Latest Studies and Practical Applications. IDEA Personal Trainer, 11(1), 15-16

- https://barbend.com/3-most-common-types-periodization-when-to-use-them/

- J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2008 Mar;48(1):65-75.

NFPT Publisher Michele G Rogers, MA, NFPT-CPT and EBFA Barefoot Training Specialist manages and coordinates educational blogs and social media content for NFPT, as well as NFPT exam development. She’s been a personal trainer and health coach for over 20 years fueled by a lifetime passion for all things health and fitness. Her mission is to raise kinesthetic awareness and nurture a mind-body connection, helping people achieve a higher state of health and wellness. After battling and conquering chronic back pain and becoming a parent, Michele aims her training approach to emphasize fluidity of movement, corrective exercise, and pain resolution. She holds a master’s degree in Applied Health Psychology from Northern Arizona University. Follow Michele on Instagram.