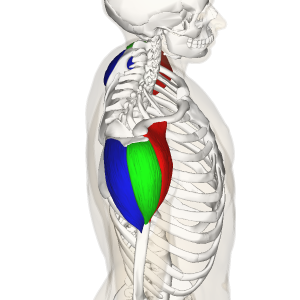

The deltoids, otherwise known as the deltoideus or shoulder muscle, consists of three distinct “heads” with very different joint actions that, when engaged simultaneously, work together to produce shoulder abduction: the anterior deltoid, the middle deltoid, and the posterior deltoid. Each fiber has a separate origin but they share one point of insertion.

What’s remarkable here, however, is that at least two studies of cadavers and healthy volunteers indicate that each head invests into the insertion via separate tendons. PET scans indicate the anterior deltoid can be divided into two segments and the posterior deltoid can be divided into four distinct segments (the middle deltoid remains a solitary unit) for a total of seven (I-VII) compartments.

This suggests and was supported by testing, that each segment’s fibers can separately perform a distinct motion from the remaining fibers.

The Anterior Deltoid

Also known as the front deltoid.

Origin: The anterior, superior surface of the lateral third portion of the clavicle. It inserts into the deltoid tuberosity on the lateral aspect midway down the humerus.

Function: The anterior deltoid works as a synergist to pectoralis major for shoulder flexion and transverse (or horizontal) adduction (as in a chest press). These fibers also assist the subscapularis and latissimus dorsi with internal rotation.

But that’s not all! When working in unison with the middle and posterior fibers, the anterior delt also performs shoulder abduction, especially when the humerus is externally rotated, as in an overhead press. In fact, it becomes the primary shoulder abductor in this position.

When medially or internally rotated, the fibers of the first segment (I) of the anterior deltoid will actually contribute to adduction, or returning from being raised in the scapular plane.

Chew on that for a moment: Anterior deltoid fibers perform shoulder flexion, transverse adduction, abduction, and adduction.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deltoid_muscle#/media/File:Deltoid_muscle_top10.png

The Middle Deltoid

Mistakenly referred to as the medial deltoid. It is not since medial refers to a location close to the midline of the body, not the “middle”. In fact, this is more accurately referred to as the lateral or side deltoid.

Origin: The lateral and superior surface of the acromion. It also inserts into the deltoid tuberosity, though somewhat posterior to the anterior deltoid.

Function: Shoulder abduction when the shoulder is medially rotated. However, when the shoulder is externally rotated, the middle deltoid assists in transverse abduction, as in a supinated wide row or a banded “W” pull.

The Posterior Deltoid

Also known as the rear deltoid.

Origin: Just inferior to the posterior border of the spine of the scapula.

Function: Transverse adduction. Assists latissimus dorsi in shoulder extension. May also contribute to shoulder external rotation, though this is not its primary role and it may become *synergistically dominant over the primary external rotators: the infraspinatus and teres minor.

The rear compartments of the rear delt, VI & VII, will also contribute to shoulder adduction.

*A note on the rear delt: Because of the synergistic dominance that is common with these fibers, they have a tendency to become overactive. However, this overactivity occurs when other shoulder muscles become over/underactive, evidenced by imbalanced posture and shoulder dysfunction. Such dysfunction, such as short pec minor/major and lats, will cause the rear delt to rest in a lengthened position. That means, stretching the muscle is not a remedy for overactivity. Instead, a static manual or self-myofascial release may reduce signs of overactivity and synergist dominance in these muscle fibers.

Unified Movement of the Deltoids

While the separate fibers of the deltoid can by synergists in several joint actions, its principle role as a single unit when all fibers contract simultaneously is shoulder abduction. When the shoulder is medially rotated, the fibers are able to contract to their maximum potential. This is one reason why the upright row is a favored shoulder movement.

However, it bears mentioning that placing the humerus into medial rotation may cause impingement of the humeral head within the glenoid fossa. Only healthy, balanced shoulders should perform this motion and with great care.

Exercising the Deltoids

As mentioned above, the one movement that will target all three heads of the deltoid is shoulder abduction. For most general fitness and weight loss clients, this is the only targeted shoulder movement that is worth programming. The compound movements for chest (push-ups, chest press, dips) and back (lat pul-down, pull-ups, chin-ups, rows) will recruit the deltoids adequately.

For those who are geared towards hypertrophy and would like to focus on developing the deltoids further, there are certainly options:

Overhead Press: The most popular compound movement for shoulders can be performed with a barbell, dumbbells, cables, or resistance bands. If you do nothing else, this movement will hit the deltoids well enough. Changing the grip to neutral as in a landmine press will externally rotate the humerus and place more emphasis on the front delt while also minimizing joint impingement. Choose this if your client experiences shoulder discomfort with a traditional overhead press.

Dumbbell or *cable front raise: Raising one or both straight arms out in front of the body into shoulder flexion will target the anterior deltoid fibers. Changing the hand position will vary the degree of fiber recruitment. Since we know that the anterior fibers assist in media (internal)l shoulder rotation, rotating the palms down into pronation will shorten the anterior fibers more than supination.

To maximize that contraction, you might start with the hands supinated and rotate into pronation by the time the arms reach 90 degrees of flexion. Be mindful to keep the shoulders depressed during this motion to reduce likelihood of humeral head impingement. If you feel uncomfortable, or “crunchy” while performing this rotation (or the front raise with any hand position) then abandon this motion.

Dumbbell or *cable lateral raise: The middle deltoid is recruited most during simple shoulder abduction with the shoulder in medial rotation. That means, outside of an overhead press, raising straight arms out into abduction in the frontal plane will also effectively recruit these fibers.

Again, the caveat here is that most shoulder joints do not like being extremely medially rotated, and the humeral head may rub or become impinged in the joint. A compromise is to keep the palms neutral during abduction. Supination is an option as well, but this will now emphasize the anterior deltoid over the middle deltoid. Finally, flexing the elbows to 90 degrees and performing abduction with dumbbells or a machine will also emphasize the middle deltoid while also minimizing joint stress.

*Using a cable will exert resistance sooner than the gravity of a free weight will, creating more muscle tension through the exercise.

Reverse Flye: Essentially transverse abduction, a reverse flye will emphasize posterior deltoid contraction, (and middle delt if the shoulders are more externally rotated) but will also recruit other back musculature such as the rhomboids, trapezius, and even levator scapulae if shoulder elevation and scapular downward rotation are an issue. This exercise should only be employed if shoulder mobility is sound and the posterior deltoid is NOT overactive.

High Pulley Row: (Or Face Pull) This variation of the row will recruit the posterior delt as a synergist to the lats. If you keep your arms and hands wide and palms supinated (causing the humerus to adduct more than when palms are neutral or pronated), then the middle delt will also fire.

Programming for Deltoids

For general fitness and weight loss clients, the focus should always be on compound movements over isolation movements. Because the shoulder joint is so vulnerable to injury compared to other joints, the deltoids in particular should not be overemphasized given the risk-benefit ratio. However, many activities of daily life involve lifting things overhead, and indeed, many people can get injured this way (like lifting a carry-on into an overhead compartment). Therefore, programming an overhead press in its many variations is probably a good idea.

For athletes or hypertrophy clients, isolation exercises can be performed with care. No one wants an injured shoulder, definitely not an athlete that utilizes the shoulder to perform his or her chosen sport. Pay attention to form, apparent discomfort wincing, or twinges. Ask for feedback from your client if he or she is unlikely to report discomfort or injury.

Performing shoulder mobility assessments is a worthwhile endeavor given the problems that tend to arise in the shoulder joint. Even programming some corrective work may be a welcome challenge for most clients. And you will have better prepared them to move forward with deltoid development.

References:

- brentbrookbush.com/articles/anatomy-articles/muscular-anatomy/deltoids/

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deltoid_muscle#cite_note-16

- www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21118198: Anatomical and functional segments of the deltoid muscle. Sakoma Y1, Sano H, Shinozaki N, Itoigawa Y, Yamamoto N, Ozaki T, Itoi E. J Anat. 2011 Feb;218(2):185-90. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01325.x. Epub 2010 Nov 30.

NFPT Publisher Michele G Rogers, MA, NFPT-CPT and EBFA Barefoot Training Specialist manages and coordinates educational blogs and social media content for NFPT, as well as NFPT exam development. She’s been a personal trainer and health coach for over 20 years fueled by a lifetime passion for all things health and fitness. Her mission is to raise kinesthetic awareness and nurture a mind-body connection, helping people achieve a higher state of health and wellness. After battling and conquering chronic back pain and becoming a parent, Michele aims her training approach to emphasize fluidity of movement, corrective exercise, and pain resolution. She holds a master’s degree in Applied Health Psychology from Northern Arizona University. Follow Michele on Instagram.